Ever wondered about the enchanting origins of historic conservatories?

With a rich history rooted in “a royal appetite and a doctor’s command,” as articulated by Alan Stein in “The Conservatory: Gardens Under Glass”, these early sanctuaries were crafted with meticulous detail, and are still the inspiration for iconic structures such as the Conservatory at Longwood Gardens, the Conservatory of Flowers, and the Palm House at Kew Gardens. While today we identify conservatories as beautiful, transparent glass structures, many are unaware the conservatory is an evolution of the Orangery; a more robust structure that first did not contain glass at all!

Let’s explore how the first conservatories were conceived.

The Early Orangeries

In the 17th and 18th Centuries, Orangeries emerged as a response to the imperative need to shield delicate plants from harsh European winters. At the recommendation of his physician, Emperor Tiberius was advised to incorporate the fruit of a plant belonging to the melon and cucumber family into his daily diet for health reasons. This directive marked the inception of the orangery, signifying a pivotal moment in its historical importance. As centuries passed, these humble havens evolved from simple, temporary structures to more permanent, decorative fixtures, designed to cradle exotic trees brought back to Europe by intrepid explorers. Initially featuring thick masonry walls and south-facing windows for optimal light and warmth, these orangeries transformed into opulent venues for gatherings, feasts, and parties, immersing guests in the fragrant allure of prized citrus trees.

In the mid-17th century, a symphony of opulence and grandeur echoed through the grounds of Versailles, France—a crescendo embodied in The Orangery of Versailles. Initially designed by the esteemed Louis Le Vau and later expanded upon by the gifted Jules Hardouin-Mansart, this early orangery served as a symbol of wealth and prestige. King Louis XIV created a collection of over 1,000 trees comprised of orange trees from his other royal houses, purchases from Spain, Portugal, and Italy, and encouraged visiting nobles seeking favor to arrive at Versailles bearing trees from their own orangeries. At the heart of this grand structure lies a central gallery adorned with barrel-vaulted ceilings, a testament to the influence of the Baroque era. The intentional creation of a space that harmonizes with the needs of delicate flora and the desires of high society guests reflects a profound appreciation for both nature and luxury.

The Mediterranean Specularia and Versailles Orangery soon gave rise to other orangeries across Europe and making the transition to more prominent fixtures in the garden – statement pieces that are not only functional, but stand as a sign of wealth and status. The Orangery at Kensington Palace is one of the early Orangeries created when the love and appreciation of this type of architecture flourished. With its red and brown brick construction and formal pediment, the building sits comfortably on the land rather than commanding it. Although the exterior is restrained, the interior, as Alan states in “The Conservatory: Gardens Under Glass”, “…leaves no doubt that it was designed for royal occupants. Distilling the essence of the lavish…”. Unlike the grandiosity of Versailles, Queen Anne’s orangery was designed as a tranquil retreat where she could entertain her friends amidst the splendid gardens beyond the palace walls.

Originally conceived as a sanctuary for orange trees, the Bowood Orangery design reflects a meticulous attention to detail and a profound understanding of both functionality and aesthetics. Architects Robert and John Adams played a pivotal role in shaping the structure, drawing inspiration from the medieval hunting lodge upon which it was built. Through meticulous expansions and renovations, the orangery evolved into a masterpiece that harmoniously blends historical roots with modern design principles of the time. Its magnificent glass windows allow natural light to flood the interior, creating a serene and inviting atmosphere for visitors. Lit by nine large, arched windows and integrated into the overall structure and design of the main house, the orangery with its collection of exotic plants and art, became a showcase.

A Pivotal Transition in Orangeries

As we move into the early 19th century, notable conservatories with expansive glass features begin to emerge. evolutions in technology, construction and the availability of materials allow architects to design with more lightweight interpretations of the orangery. Notable conservatories begin to emerge such as the Castle Ashby Orangery, the Conservatory at Alton Towers, and the great Conservatory at Syon Park.

Alton Towers, a renowned landmark, exemplifies this transformative phase in conservatory architecture. With its breathtaking landscape and architectural prowess, Alton Towers redefined the essence of orangeries. The fusion of natural splendor and architectural ingenuity at Alton Towers symbolizes a departure from the traditional orangery concept towards a more expansive and immersive botanical experience.

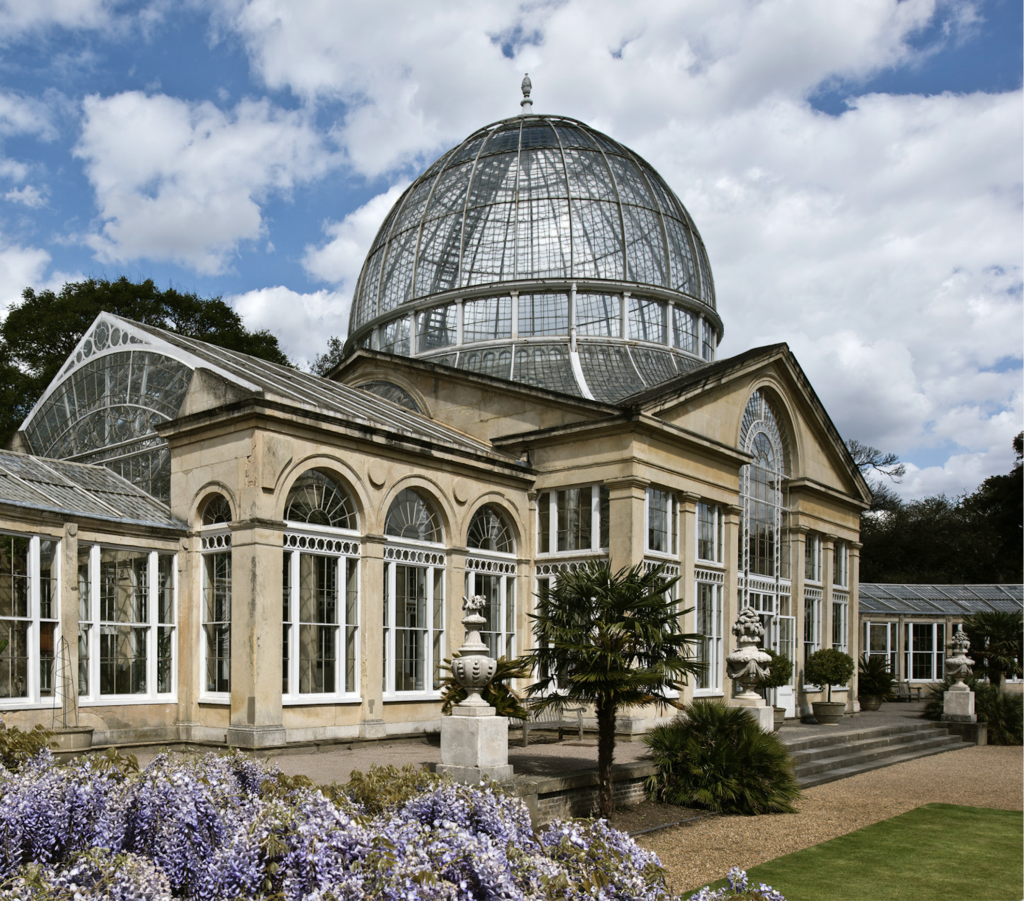

Perhaps the most pivotal transition between the orangery and conservatory is displayed at the great Syon Park. This iconic structure encapsulating the essence of both conservatories and orangeries in a unique blend.

Notice the robust stone structure with large glass front-facing windows mimic the traditional orangery style, then as our gaze moves from left to right, glass begins to take over the majority of the roof and structure. These end caps display this transition beautifully.

Through its innovative design and harmonious integration with its surroundings, Syon Park contributes to the rich tapestry of botanical history, inspiring future generations of architects and garden enthusiasts alike.

Captivated by the rich history of conservatories? Delve deeper into their fascinating journey by obtaining a personal copy of “The Conservatory: Gardens Under Glass” and unravel the captivating narrative behind these architectural masterpieces.